The latest release of results from the National Health Security Preparedness Index occurs at an unprecedented time in global public health history. States and communities are actively responding to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (COVID-19), while anticipating the many other hazardous events that may occur during 2020 and actively exploring ways to refresh depleted personnel and resources. To help navigate this era of uncertainty, we have streamlined the release of 2020 Index results in order to put updated information into the hands of emergency preparedness stakeholders as quickly as possible.

What Can Be Learned from Updated Results?

Results from the 2020 release of the Index show that national health security capabilities continue to gain strength, but at a rate that has slowed down over time. Most states experienced improvements in health security levels over the past year, but at widely varying levels. Large geographic differences in preparedness remain, and these differences have grown larger over time in selected domains. Jurisdictions are responding to a growing array of risks and hazards by stretching constrained human, financial, and technological resources and making difficult trade-offs.

How can states and communities use this updated information? Coronavirus transmissions appear to be leveling off in a growing number of U.S. regions, giving these areas some breathing room and a chance to take stock of their capabilities and needs. With a large set of 130 measures, the Index allows users to identify strengths and weaknesses across a broad range of sectors and capabilities.

As new resources become available through federal coronavirus aid packages, the Index can help emergency preparedness stakeholders identify where vulnerabilities exist and where reinforcements are most urgently needed. Users can quickly identify leading states in each domain of preparedness and in regions across the United States, allowing for peer networking and cross-jurisdictional learning to occur.

What Can Findings Tell Us About COVID-19 Response?

The Index includes many measures that are directly relevant to coronavirus response efforts, including measures of laboratory testing capabilities, epidemiologist staffing, hospital surge capacity, nursing home infection control, household broadband access, and employer-provided paid time off. Effective responses to COVID-19 require coordination of resources across a broad range of public and private sectors. The Index integrates data from a broad range of sectors to offer a comprehensive view of preparedness.

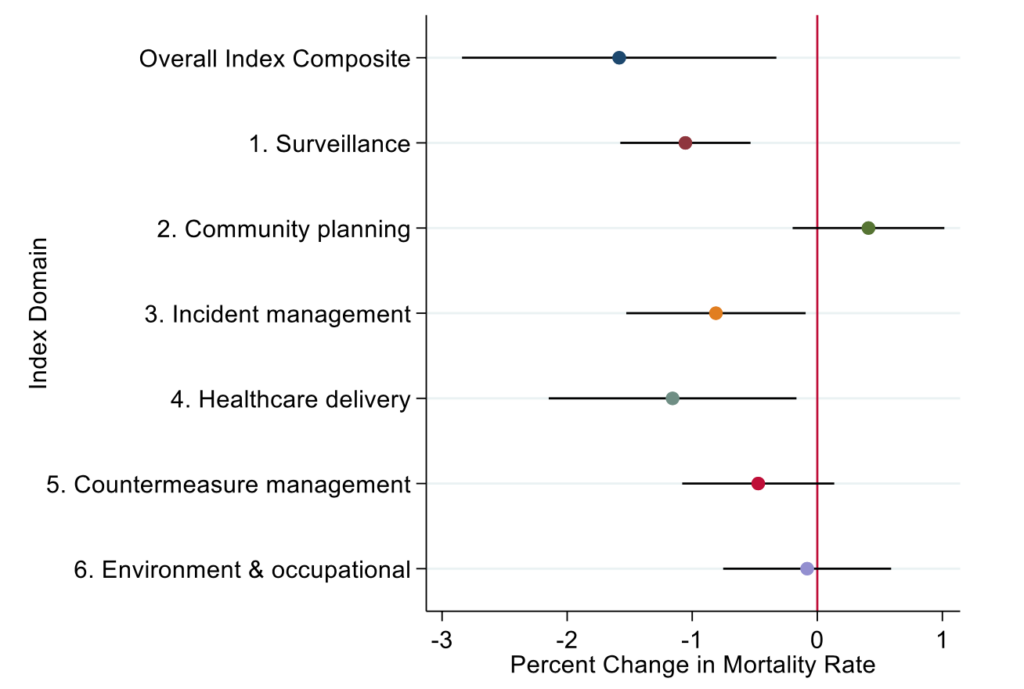

Figure: Higher Scores on the 2020 Health Security Index Are Associated with Significantly Lower Risk-adjusted County COVID-19 Mortality Rates

Note: point estimates with 95% confidence intervals are shown as horizontal lines. Estimates are derived from risk-adjusted mortality regression models using generalized estimating equations.

To gain additional perspectives on pandemic response, Index results can be linked with emerging state and local data on COVID-19 (see figure). To date, states with higher health security levels have experienced significantly lower risk-adjusted COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 population – an encouraging trend that can be monitored over time. The figure above shows how county-level risk-adjusted mortality rates change in response to a one point increase in Index scores. These results can help stakeholders craft targeted responses for regions that face higher mortality risks combined with lower preparedness levels.

What Index Changes Were Introduced in 2020?

The Index measurement set and methodology remain virtually unchanged from last year. We introduced one new measure into the Index based on recommendations from the field: a measure of nursing home compliance with federal standards for infection control. This addition appears particularly relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic, given the heightened infection rates observed in long-term care facilities across the United States.

One notable change to our dissemination process this year is the rethinking of the “Index preview period” used in previous years to give emergency preparedness stakeholders an early look at the results and a structured process to provide feedback. To avoid placing additional demands on these officials during the COVID-19 response and to provide information as quickly as possible to the field, we are releasing the results directly to the field without holding a full review and comment period. One downside of this minimally invasive approach, of course, is that we have fewer opportunities to screen for possible errors in the many data sources used in the Index. Such errors have been rare in previous releases of the Index, but they occasionally do occur in some data sources, particularly those that rely on self-reported information from agencies and facilities. For this reason, we invite Index users to ask questions and provide feedback on an ongoing basis at any time that is convenient by sending an email to our research team at [email protected]. If we identify the need to correct any data source based on this feedback, we will release corrections as soon as possible on the Index website.

We hope you find useful information and new insight about the geography and dynamics of health security in this latest release of the Index. We look forward to incorporating the lessons learned from current health security experiences into future releases of the Index.

Glen P. Mays PhD, MPH is the chair and a professor in the Department of Health Systems, Management and Policy in the Colorado School of Public Health at CU Anschutz. His research examines delivery and financing systems for health services, with a focus on estimating their effects on population health and economic efficiency.